We use historical events as examples to learn from, but is it possible to acquire a true understanding of a historical event?

The answer is important because we use that understanding to learn by example, and identify patterns of cause and effect. Is it possible for a normal person to do this, or does it require training, lots of time, or special skills? Is it impossible for everyone?

I started thinking about this when I had the following thought:

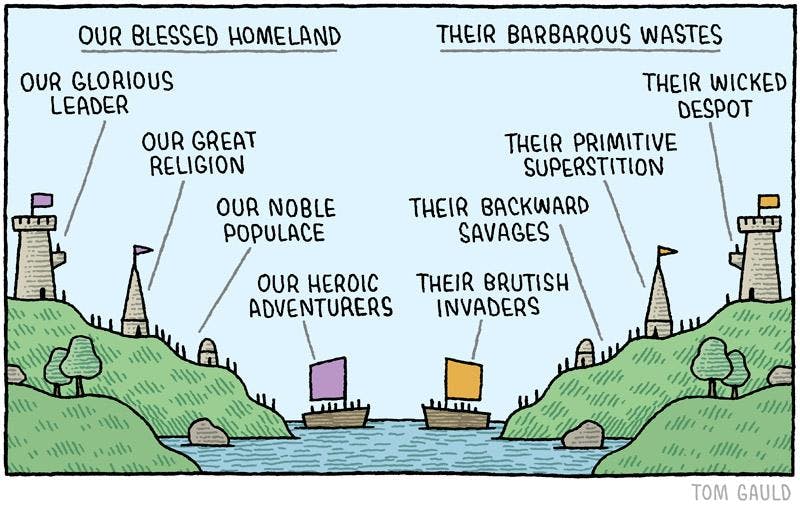

When we think we understand why something historical happened, all we've probably done is accept a story that seems plausible.

Limitations and Reliability

An account of an event must necessarily be a simplification - not all details can be recorded or learned. This is ok because most details are not pertinent and have no meaningful consequences.

But how do we choose which details are included, and how do we verify that the details were chosen correctly?

How can we be sure that a lesson or conclusion based on historical events is reliable?

Hypothetical model

The truthfulness of a historical story could be thought of as a value on a scale ranging from completely false to perfectly true. I think that there are mechanisms that push popular or resilient narratives towards the middle of this scale and away from either extreme.

As a version of a story approaches the dishonest end it will contain an increasing number of errors or omit an increasing number of pertinent facts. This has the effect of:

- Increasing the likelihood and frequency of someone hearing the story and rebutting its assertions.

- Making it harder to align the assertions and implications with existing understandings of reality.

At the opposite end of the scale, a story is unlikely to be comprehensively honest because:

- Adding truth requires adding complexity. It is easier to create or capture a simple story than a complicated story.

- As a story's detail and depth increases so do the resources required to communicate it. Each narrative is competing for attention and a complex story requires more resources to broadcast and listen to than a simple story. Those with the resources to do so will want the story to benefit them in some way.

This creates incentives to omit inconvenient truths and distractions.

Implications

I think that there is unfortunately no substitute for the hard work of coordinating disparate information, because the truthiness of a conclusion is generally proportional to the inconvenience of the effort spent forming it.

We are predisposed to choose convenience over inconvenience and this enables:

- History to be written by the "winning side", who have more resources than the "losing side".

- Complex events to be simplified into expedient and bite-sized narratives.

As time passes, the practical benefit of holding a view that differs from a popular narrative decreases. This reduces any incentive to challenge a popular view.

This creates a feedback loop that makes it increasingly difficult for a younger generation to discover information about historical events that challenge a popular narrative.

An heuristic

How much evidence did I collect myself, that wasn't brought to my attention by an algorithm or by someone else?

Awkward questions

- Was WW2 a battle of the good against the bad, or the bad against the really bad, or something else?

- Why did the Allies win WW2?

- Was the influence of government on social freedoms in America 100 years ago dissimilar to China today?

- Racial and ethnic discrimination was normal 100 years ago - it appears to have been so universally accepted that I'm led to question the presuppositions of modern attitudes about human nature and morality.

[